|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

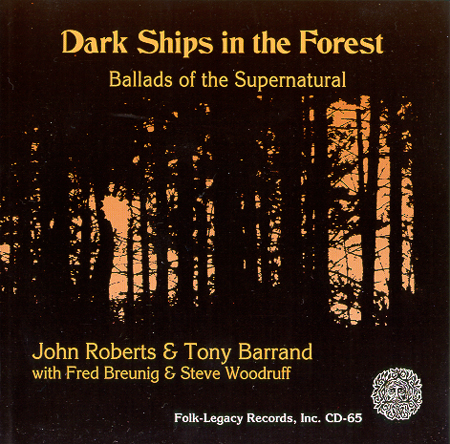

FSI-65 Dark Ships in the Forest | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lyrics for each song can be accessed by following the links in the playlist above. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TECHNICAL INFORMATION | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Special thanks to our guest musicians Fred Brunig and Steve Woodruff, who each added fiddle and button accordion to this recording. And to all the members of the Haggerty and Paton households who put us up, put up with us, and made this all possible, from LP to CD. Notes by John Roberts and Tony Barrand |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SONG NOTES | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

As children, we are as familiar with the story-world of elves, giants, witches and ghosts as we are with the world of reality around us. This kind of fantasy plays a major role in our growing up, but as we mature it seems to get shuttled furthe and further into the backs of our minds, closeted up, to be released only for the occasional entertainment of our own children. But it is precisely this variety of fantasy which provided a major part of the entertainment of days gone by. Songs and tales, carried in a family tradition intermittently refreshed by itinerant musicians and raconteurs, were full of bizarre encounters between young men and water nymphs, knights and dragons, fairy queens and magicians; and manyt of these same ballads, as song or story, have been carried down to us through the same family traditions. The songs we sing here were born of this stock. Because of our biases, they are based on English and English-derived tradition, or are English in style or spirit (as it were). Many of them are filled unashamedly wiht the fantastical events of the balladry of yesteryear, others carry only faint indications of some long-gone past, of unnatural hammenings, of pagan ritual, and of disconcerting power. In the primal forest of folk songs, these are our dark ships. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

John & Tony |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Oak, Ash and Thorn. Rudyard Kipling's "A Tree Song" sets the scene for the stories and poems of Puck of Pook's Hill. This setting is by the late Peter Bellamy, to his own tune. We also use the song as a scene setter, a "calling-on song." The magic of trees lies deep in the roots of Druidic religion and mythology, and the oak, ash and thorn are central characters of the bardic tree-alphabets. Much of this tree lore has survived in folk tales, in English as well as in Celtic tradition. The Broomfield Wager. Cyril Poacher, our source for this "pub" version of a most venerable ballad, was a regular at the Saturday night sing-songs in The Ship Inn, at Blaxhall in Suffolk. The somewhat garbled nature of the story line is heightened by the mysterious "Hold the wheel" chorus, apparently the result of a misunderstanding of "had his will" by a visiting (and presumably inebriated) yachtsman. It stuck. The Wife of Usher's Well. Scotland would seem to be the birthplace of this ballad, though, like many of the Child ballads, it has flourished better on this side of the Atlantic. Our variant of this ballad (a rare English one) was transcribed by Ralph Vaughan Williams from a phonograph recording of a Mrs. Loveridge of Dilwyn. Tom of Bedlam. More properly titled "Mad Maudlin's Search for her Tom of Bedlam," this song does not seem to have had much currency in the tradition. It has been dug up from print and was popularized by Tom Gilfellon of the High Level Ranters. The Dreadful Ghost. In a number of songs, a ship refuses to sail because of the presence of a Jonah, an evil-doer who must be sacrificed before the vessel can proceed. Our version of this one is Canadian, collected by Helen Creighton in the Maritimes, collated with Newfoundland texts gathered by Kenneth Peacock. Jean Ritchie, on hearing it sung, remarked that it must have been written by a woman. The Foggy Dew. Though hardly supernatural this ballad does have its elements of mystery, particularly in the meaning of the phrase "foggy dew." Does it really symbolize virginity, or is it more properly the "bugaboo" of Amarican variants? Here is our ghost, and one in all probability contrived by the artful lover, but we still don't know where the foggy dew comes from. This version of the song, however, does come from the vast repertoire of Harry Cox, of Catfield, Norfolk. The Derby Ram. Found in Mother Goose, widely known in England, America and Australia, and even, as "Didn't He Ramble?" as a New Orleans jazz classic, this has become one of the most popular songs in the English language. A.L. Lloyd describes it as a "randy animal-guiser song" which in these latter days survives as a "bawdy anthem for beery students or soldiers coming home on leave." He identifies our monstrous beast as the devil, the "genial horned deity" still half-worshipped in pagan ritual by the medieval peasant, oppressed by church and state alike. The Maid on the Shore. Our version of this jolly little tale, one much better preserved in the northeast of America than in Britain, comes from Etson Van Wagner of Roscoe, NY, via Norman Cazden's Abelard Song Book. Reynardine. Irish in sentiment and almost certainly so in origin, this song conjures visions of the folk tale's Mr. Fox, dismembering the young girls he has seduced away to his forest mansion, a sylvan Bluebeard whose bestial cruelty is matched only by his cunning charm. The False Lady. In common with other American examples, this New England version of "Young Hunting" has lost its ending, in which the heroine is burned at the stake for her transgressions. Jealousy is often a good enough motive for murder, but death is still a rather high price to pay for a little white lie. Polly Vaughn. Child apparently did not think enough of this one to include it in his canon; Robert Jaieson, a Scot who published his collection of ballads in 1806, characterized it as "one of the very lowest descriptions of vulgar modern English ballads." Our heroine is a modern relative of the swan-maiden or enchanged doe: maiden by day, swan by night, killed with a majic gun, reappearing as a spirit to clear her lover - this is the stuff of epic fairy tales. Our tune comes from Carrie Grover of Bethel, Maine; the text is from Harry Cox and A.L. Lloyd. The Two Magicians. The idea of changing shape to avoid capture and outwit or kill a pursuer is common in European folk tale. In Britain, the tales spawned this ballad. A.L. Lloyd writes (Sing Out! 18/1): "Eventually the ballad dwindled away, but it seemed too good a song to remain unsused; so I brushed it up and fitted a tune, and now it appears to have started a new life." |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

© Golden Hind Music |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||