|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

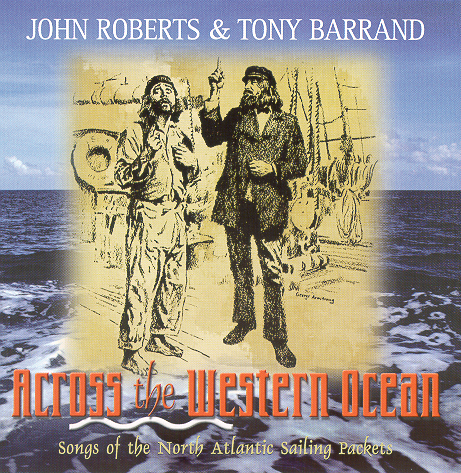

ST-4 Across the Western Ocean | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lyrics for each song can be accessed by following the links in the playlist above. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TECHNICAL INFORMATION | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

With David Jones, Gerret Warner, Jeff Warner Produced by John Roberts & Tony Barrand All selections traditional |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CD NOTES | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

"It was snowing hard that morning;" wrote Albion, "that in itself might easily have been taken as an excuse for delay. As St. Paul's clock struck ten, however, Captain Watkinson gave the signal, the sails were trimmed, the lines cast off and the 'James Monroe' slid into the stream on time as advertised." And thus, on January 5th, 1818, the departure of the first packet ship to leave New York marked the only improvement in transatlantic travel since the 'Mayflower', an achievement ranking with the later triumphs of Marconi and Lindbergh. The owners of the Black Ball Line of sailing packets had decided that freight and passengers between New York and Liverpool could and should be shipped on a fast, regular schedule, thus breaking with a long tradition of cautious, fair-weather sailing. They promised that one ship would sail from New York on the fifth of every month, and one from Liverpool on the first. Four ships ('Amity', 'Pacific', 'Courier', and the 'James Monroe') were equipped for this purpose, and each, the advertisement claimed, had ample storage space for freight as well as "uncommonly extensive and commodious" accommodations for passengers. Within three years the Black Ball Line had started another line of four ships, under the insignia of a black ball painted or sewn onto the foretopsail, and the Red Cross Line and the Liverpool Swallowtail Line had opened up in competition, thus providing a weekly service in each direction. Establishing and maintaining a regular service on the unpredictable Western Ocean placed great demands on ships and men. American designers were equal to the challenge and their ships dominated the North Atlantic trade, the fierce competition accelerating their design and performance to unprecedented heights. In 1819 the 'Savannah' steamed (but mostly sailed) its way across the North Atlantic, but it was to be fifty years before the steamships forced the packets out of business. By 1870 the square-rigged sailing ship was still profitable on the longer runs to China and Australia, but the day of the clipper was a short one, and steam was soon to replace even these "ocean greyhounds." To take advantage of every change in the weather, the fully-coordinated performance of the crew was essential. The rhythm for their labors was provided by the shantyman, making up verse after verse to humor the crew, their raucous choruses punctuated with the rhythm of the job at hand. The shantyman's art flourished in this period, and it is largely his songs that are presented here, as shanties to sweat to, or forebitters sung for the pleasure of singing and listening, in more relaxed hours. The Ships Talk of fast sailing ships immediately brings to mind the clipper, but technically a ship could be both a packet and a clipper. Albion coins a simple analogy to illustrate the difference: "The packet, like the postman [mailman], represents a functional distinction implying regularity of service on a particular run. The clipper, like the thin man, represents a structural distinction; it implied a streamlined vessel designed for speed on the long California and China runs." From the beginning the packet enterprise depended on speed, and the American merchant marine already had a reputation for carrying full sail when other ships were lying hove to. The packets themselves were not fast in light winds, but they did not sail in the latitudes of light winds. The owners wanted ships that could carry profitable cargoes, and expected their captains to make up for the speed that was deliberately lost in their rugged construction. This they did by driving their vessels day and night, carrying, at all times, as much sail as weather and ship would allow. The packets were noted for their strength, especially those designed by Donald McKay, who was responsible for many famous packets and clippers, such as the 'Flying Cloud' and the 'Sovereign of the Seas'. These ships were at their best beating to windward in a gale. Their yards could be braced around more sharply than in most other ships, and as a consequence they could sail closer to the wind. Thus, tacking into the strong North Atlantic winds on the westward run, they could take fewer tacks to cover the same distance. Basil Lubbock reports a race between the fast iron clipper 'Baron Colonsay' and the Swallowtail packet 'E.W. Stetson': "It was dead beat up and although the 'Baron Colonsay' went through the water about three knots faster than the 'Stetson', the Yankee could head a point or more higher, with the result that after a tussle of several days duration, they took their pilot boats together." In addition, packets were built with full rounded bows above the waterline so that they rose to oncoming seas and stayed dry, whereas the clipper ships, with their sharp streamlined bows, cut into the waves and shipped water constantly. The owners stood to profit from building these stout-hulled vessels. By 1835 the gross earnings of a packet stood at about $30,000 per annum, and this on an initial outlay of less than $50,000 for a new one. Albion remarks that while the clippers (three hundred of them built in one decade) may have received an unfair share of the romance of sailing ships, their history would probably be written in red ink. On the other hand, there were only a hundred and fifty packets spanning a thirty year period, but almost all of them made rich men of their owners. The Captains It is apparent that the fast sailing times of the packets had as much to do with their captains as with their designers. A case in point is the famous 'Dreadnought' built especially for Captain Samuel Samuels. He wanted a vessel with the power and strength to carry a press of sail in the strongest wind. His wish was granted, for it required a gale to show the 'Dreadnought' at her best, and on such occasions she was an extraordinary ship. "Many a time," writes Captain Samueis, "I have been told that the crews of other vessels, lying hove to, could see our keel as we jumped from sea to sea under every rag we could carry." Seamen called her the "Flying Dutchman" or the "Wild Boat of the Atlantic," and under her captain's guidance she made an incredible eastbound passage of 9 days, 17 hours, pilot to pilot. Captain Samuels, like many of his fellow packet captains, was a New England autocrat who was equally at ease lashed to the ship during a gale, putting down a mutiny with a pistol in each hand, or serving as host at the dinner table to the elite of American and European society. The Black Ball line had specifically abolished the custom of giving its captains a share of the profits, and instituted a system of hiring, rewarding and firing all its employees on their capabilities and merit. Even so, many of the captains became rich men before the age of thirty-five. They were treated as celebrities on both sides of the Atlantic, with their arrivals and departures, record and average voyages reported and argued over with schoolboy passion. One effusive correspondent went so far as to describe a new packet as "the noblest work of man," and her commander as "the noblest work of God." The Crews For all the hero-worship, men like Samuels and the "Bucko" mates who served under them were hard and cruel in their treatment of their crews. There were those, however, who rejoiced in this arduous life. These "packet-rats," as they were called, sailed in "any man's ship," and the man who could stand the belaying pin and the knuckle duster hardly gave a thought to the weather. The packet-rats were almost always Yankees and they scorned "soft" ships, such as those of the British Merchant Marine, which conformed to a government Merchant Shipping Act that laid down careful protocols concerning the responsibilities of seamen and owners. It even specified that the sailor was to be issued a ration of limejuice every tenth day at sea, to ward off scurvy. The American seamen thought this was ridiculous and forever labelled the English "Limejuicer," or "Limey." But mostly the crews consisted of "joskins," or "raynecks," those unfortunate landsmen who had fallen into the hands of the dockside "crimps" who made their living providing the packet captains with a crew, for few competent seamen would volunteer to ship out on a packet. The methods of these crimps varied. Paddy West in Liverpool became famous for giving many a young and, apparently, naive landsman a complete deepwater experience within the confines of his own home; in San Francisco "Shanghai" Brown developed the use of drugged whisky into a profitable art. This example was soon followed by his counterparts in New York. "Ships' crews," Brinnin writes, "in the eyes of many captains and their employers, were species of the subhuman. Driven like slaves, taught to obey commands and whips like circus animals, their working lives were briefer than those of men in any other following. From the fecal alleys of slums ashore they were trundled into the galleys of slums at sea." Captain Samuels in 'From Forecastle to Cabin' echoes this opinion of the common seaman, and Captain Arthur Clark no less so, though a little more magnanimously: "The way to deal with these ingrates was to see they were kicked and beaten for all infringements of shipboard rules, and infractions of the captain's whims... Yet for all their moral rottenness, these rascals were splendid fellows to make and shorten sail in heavy weather on the Western Ocean." This kind of treatment was typical of 19th Century attitudes of employers in their employees, or to the working class in general, but it is perhaps surprising that it was just as evident in the practices of the new republic as it was in the factories of England. The great excuse for it was, of course, profit for the owners, rationalized as being ultimately good for the general economy. And they profited not at the expense of the rich, the eminent and the literati, who travelled at leisure across the Western Ocean in staterooms with pleasant saloons and four meals a day at the captain's table, but with cargoes of cotton, machined goods and, in the same hold, the emigrants. The Emigrants In the years between 1815 and 1854, a total of 4,116,985 emigrants left the British ports, well over half of these in the years from 1846 to 1854. The fare for an emigrant was four English pounds, or approximately nineteen dollars. For this the company provided transportation, a cooking fire in good weather, (one fire for, perhaps, five hundred persons) drinking water that probably tasted of the previous contents of the cask, and a narrow space to put a bed. The emigrants had to provide their own food, cooking utensils and bedding with little or no advance information about provisions for a sea voyage. A westbound passage could take anywhere from thirteen to sixty days or more, and if their supplies of food ran out or went bad that was just tough luck. Many of them, and their families who stayed at home, were probably most afraid of shipwreck and seasickness. As to the former, in point of fact the packets had a remarkable maritime safety record. Of course, there are many ways of playing with and presenting the relevant statistics: Albion notes that although one in six of the packet ships themselves was lost, only twenty-two out of nearly six thousand crossings ended in shipwreck. Any wrecks that did occur were reported imaginatively by the press, with artists' impressions of the scene. Yet the emigrants actually had far more to fear from the conditions in which they were expected to exist for the duration of the voyage. The owners bundled everyone, man, woman or child, into the large cargo holds with no provision for privacy or sanitation, and as early as 1819 the packets were arriving with as many as ten percent of their steerage passengers dead from starvation or disease. The situation became so had that the Port of New York began to charge packet captains ten dollars for every corpse they delivered to the New World. It was twenty years before the British and American governments enacted legislation to curb the spread of disease and prevent people from starving at sea. This code required the owners to provide adequate sleeping space, 14 square feet per person, (which some wag netted "room enough to die in") and a minimum weekly ration of 21 quarts of water, 2 1/2 pounds of biscuits, 1 pound of wheat flour, 5 pounds of oatmeal, 2 pounds of rice and two pounds of molasses. This cost the company all of twenty cents a day per passenger, and might be contrasted with the style and grace attending the cabin passenger who paid forty pounds ($186) for the trip, and four times a day sat down to a meal that would keep an emigrant for a week. The packet carried live sheep, goats, pigs, hens and usually a cow to provide for the cabin passengers; bags of yellow meal were loaded for those in steerage. The marine historian W. S. Lindsay creates a vivid picture of a hold crowded with emigrants, even though he was typically Victorian in his total tack of sympathy for their plight: "The filthy state of these ships was worse than anything that could be imagined. It was scarcely possible to induce the passengers to sweep the decks after their meals, or to be decent with respect to the common wants of nature; in many cases, in bad weather, when they could not go on deck, their health suffered so much that their strength was gone, and they had not the power to help themselves. Hence, "between decks" was like a loathsome dungeon. When the hatchways were opened under which people were stowed, the steam rose, end the stench was like that from a pen of pigs. The few beds they had were in a dreadful state for the straw, once wet with sea water, soon rotted; besides which they used the between decks for all sorts of filthy purposes." This same unsympathetic attitude was responsible for maintaining the conditions in which cholera and typhus (or "ship") fever could spread. Lubbock reports that the year of 1853 was an especially bad year to travel. "The ship 'Washington', he says, "arrived at New York from Liverpool in October, 1853, with cholera raging aboard. Nearly 100 emigrants had died during the passage and there were 60 cases on board when she arrived. Of other ships arriving that Autumn, the 'William Tapscott' (named, incidentally, after one of the busiest agents in Liverpool responsible for shipping emigrants under these conditions) had 65 deaths; the 'American Union' 80; the 'Centurion' 42; the 'Calhoun' 54; the 'Corinthian', from Havre, 41; the 'Statesman', from Antwerp, 25; the 'Delaware', from Bremen, 15; and the 'Gottenburg' (a steamship) from Hamburg, 27 deaths." The dangers of disease, starvation, seasickness and shipwreck did not, however, deter people from seeking a better life in the New World; nor did it deter the rich and eminent from the adventure of a North Atlantic crossing. The packet captains, the historians, and some of the best of the 19th Century writers, including Mark Twain, Fennimore Cooper, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Alexis de Toqueville, have amply told the priveleged side of the story of the packet era. They all travelled cabin class. There are few sympathetic accounts of the crews and the emigrants, although Brinnin's 'Sway of the Grand Saloon' and Melville's 'Redburn' are important contributions. The crews themselves wrote no books, but they did leave us their songs. The Songs The songs sung on board the packet ships (by the crews, at least) can be roughly divided into the categories of shanty (or "chantey") and forebitter. The shanty was a work song used exclusively to provide the rhythm for the crew working on deck or up in the rigging. Some jobs, such as hauling up the anchor with the capstan, were long, slow and arduous, but maintained an even rhythm. Here the shantyman would set the tempo with a fairly long shanty, usually telling a coherent story, the verses interspersed with drawn-out choruses sung by the men as they walked around. Other tasks, such as setting a heavy sail, particularly in wet weather, were less regular in rhythm. For work like this, the shantyman would set some short, quick pulls to get the job under way, settling into a slower and more even rhythm as the yardarm went up. Finally, to get the maximum effort out of his crew for the last few pulls to "sweat" the yard up as far as it could go, he would change his shanty yet again. These shanties were more extemporaneous, the shantyman making up, or adapting from his stock of "floating" verses, enough extra verses about the common framework to make his shanty last just the length of the job, or section of the job, in hand. Some tasks were short enough that usually only one verse was required. "Bunting" the sail up to the yard, so that it might be secured there ("clewed up") when temporarily out of use, might need only one synchronized pull. The shantyman might lead off with, "To my way, hay, hay," the crew responding with a screamed "Ya!" as the sail was lifted, and finish with, "We'll pay Paddy Doyle for his boots," as something of a "verse." If the operation was not satisfactory, the shanty could be repeated with a different verse. The forebitters were sung in a more relaxed atmosphere, in off-duty hours in the crew's cramped quarters beneath the forecastle head. On a rough passage such periods of relaxation were a rare luxury, since major changes of sail required the labors of the entire crew, the off-duty as well as the on-duty watch. In steadier weather, however, there was time enough to sing forebitters as well as to sleep. These were often popular ballads from the shore, and many would have been accompanied with fiddle, banjo, or other portable (and hopefully, durable) instrument. Our selection includes both kinds of song, though the shanties are not sung exactly as they would have been rendered on deck. Rather than recreate the timings of the tasks, we have sung them with a more regular beat, and faster than would have been practical for their services as work songs. The sets, however, have been chosen as both typical of the period, and relevant to the conditions of the time. The shantyman's art was a delicate one: he had to draw the line between the pace the men wanted to work at and the speed the mate required. Paid by both company and crew, he could not afford to step off this narrow path. He had to cajole and harangue his crew as best he was able, keeping the men amused and the mate happy. These are his verses. Bibliography The references listed here are the major sources of our information. Other less general references are given in the text. As far as the songs are concerned, we have not tried to be comprehensive in our catalogue of published variants, and, at least for the batter-known songs, we have satisfied ourselves with mentioning a few easily accessible sources, listed here. Again, some more specialized references are given in the text. General: Albion, Richard Greenhalgh: 'Square-Riggers on Schedule', Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press, 1939. Songs: Colcord, Joanna C.: 'Songs of American Sailormen', New York: Oak Publications, 1964. The South Street Seaport Museum in New York City, along with the Whaling Museum in New Bedford and the seaports at Mystic and San Francisco, is one of the lively organizations dedicated to the preservation of the history of the age of the great sailing ships. All of these organizations need support from outside sources, and South Street most certainty merits it. The Seaport Museum has made available such excellent books and record albums as McKay's history of South Street (see bibliography) and Louis Killen's '50 South by 50 South: Songs of the Cape Horn Road'. In New York, on South Street, it is still possible to stand on piers that knew the comings and goings of such famous packets as the 'Dreadnought' and the 'Henry Clay', and feel the same call that sent them scudding across the Western Ocean. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SONG NOTES | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Introduction The James Monroe sails from New York. (Based on information in Albion, p.22). NEW YORK GIRLS Also known as 'Can't You Dance the Polka?' this song achieved considerable popularity to the folk song revival of the late fifties and early sixties. On the packets it was used as a capstan shanty, though here it is sung more as a forebitter. This set is culled from one of the versions given by Hugill, and, in common with many other forebitters, gives an account of Jack Tar's treatment on shore at the hands of the "doxies," ladies whose livelihood depended on keeping him entertained, but whose honesty and trustworthiness as companions was sometimes questionable. Other versions are given by Colcord and Doerflinger. Captain Samuels on his sailors Captain Samuel Samuels, of the 'Dreadnought', gives an appreciation of the qualities of the Liverpool packet sailors. (From Samuel Samuels: 'From Forecastle to Cabin', New York: Harper & Bros., 1887). BLOW THE MAN DOWN Another very popular shanty, the refrain of which has been married to several different texts, 'Blow the Man Down' was used primarily for work on the halyards, (or "halliards") on the long, slow task of hoisting the heavy yards and the courses of canvas sail. Our version is again taken from Hugill, though Colcord and Doerflinger each print several variants. The verses recount some of the treatment accorded to the sailors on the packet ships, perhaps only slightly exaggerated by the shantyman. Impressions of a first voyage This "extract from the diary of a lady passenger" captures some of the discomforts and discomfiture that a member of "society" might well have encountered on a packet voyage. Her situation, however, was luxurious compared with the travelling conditions of the emigrants. And who knows, her exposure to the charms of the rough-and-ready packet-rats might even have broadened her mind a bit, however unwillingly she endured the educational process. (Inspired by Brinnin, p.20). THE CRAYFISH This is undoubtedly one of the most widespread ditties of the English language, though its coarseness, and perhaps its superficial lack of literary value, have kept it from appearing too often in print. Although versions have been reported in the 'Journal of the Folk Song Society', only the tunes are printed, the words being dismissed as too coarse and vulgar even for that scholarly publication. Sometimes known as 'The Lobster' or 'The Crabfish', 'The Crayfish' as sung here is in fact Australian, coming to us via John "Fud" Benson, who learned it in Newport, RI from Jock Stirrock, a sailor an one of the recent Australian America's Cup contenders. THE BLACK COOK Before the advent of our more enlightened attitudes towards medical research, it was impossible for doctors to acquire, by legal means, corpses for dissection, this practice being prohibited by laws emanating from the strictures of the Church. If a doctor needed a corpse, a commodity which, after all, might well be considered essential to his research, then he was forced to go outside the law. In the Midlands of England, the robbing of new graves was commonplace; in a coastal town, the opportunity to obtain a recently deceased, unburied cadaver must have been a well-nigh irresistable temptation to a medical man. The song itself is a rare one, and as far as we can determine has been collected in the field only four times, though it does appear on an Irish broadside in Cecil Sharp House (the headquarters of the English Folk Dance and Song Society). Three of the four oral versions are Canadian, collected by Edith Fowke, Helen Creighton and in Newfoundland by Kenneth Peacock, in whose book ('Songs of the Newfoundland Outports', Ottawa: Queen's Printer, 1965) we first came across it. The version presented here is essentially Peacock's, although some of the text has been collated with the Pennsylvania variant collected by Ellen Steckert, and since printed in Goldstein, Kenneth S. and Byington, Robert H. (eds.): 'Two Penny Ballads and Four Dollar Whiskey: A Pennsylvania Folklore Miscellany', Hatboro, Penn.: Folklore Associates, 1966. THE LIMEJUICE SHIP Hugill prints this song, a tongue-in-cheek eulogy of conditions aboard British ships. Thanks to a series of Merchant Shipping Acts, these conditions became well regulated, eventually reaching the point where sailors were issued rations of limejuice to counteract the scurvy, all too common among deepwater sailors. Their American counterparts, with no such laws, derided this practice as "soft," hence the nickname "Limejuicer," or "Limey," which has stuck to this day. The major proponent of these legal reforms was Samuel Plimsoll, best remembered for the "Plimsoll Line," the loading mark painted on the aide of every ship, another innovation of the period which has stayed with us. The wreck of the Staffordshire The safety record of the packets was actually nowhere near as bed as was generally believed, for any maritime disaster was taken as a license for sensationalistic reporting, as this clipping from the New York Evening Post illustrates. Shipwrecks were inevitable, but it was still to be a long time before passenger-carrying ships would carry an adequate number of lifeboats. This lesson was still apparently unlearned when the 'Titanic' sailed from Liverpool. (From Lubbock, p.40). THE FLYING DUTCHMAN The legend of the "Flying Dutchman" is a common one in many European countries, and its story has been used in novel, melodrama, opera and movie. In the most common British version, Vanderdecken, a Dutch sea captain, angered by continually adverse winds, swears a blasphemous oath ("by all the devils") that he will double the Cape of Good Hope if it takes him till Doomsday. For this profanity he is condemned by God or Devil (it is never clear which) to his self-appointed fate. His ghost ship is rarely seen, and then only in stormy seas, beating in against the wind under full sail - and bad luck to the ship which sights her. This latter ship, itself often becalmed, is sometimes entrusted with letters addressed to people long dead. Although in the British melodramas the curse is absolute, in other versions Vanderdecken is allowed on shore every seven years, in hopes of breaking his curse by wooing a lady who will be faithful to him unto death. In Wagner's opera, for example, he manages to achieve this salvation. In the German legend the protagonist, von Falkenberg, is condemned to sail the North Sea in a ship with no helm or steersman, playing dice with the Devil for his soul. According to Sir Walter Scott, the 'Flying Dutchman' was a bullion ship aboard of which a murder was committed, the plague subsequently broke out among the crew, and all ports were closed to the ill-fated craft. The only recent printed source for the song seems to be Doerflinger, who obtained his set from Richard Maitland, then retired at Sailor's Snug Harbor, New York. Broadside variants are to be found in the Harvard Library. A song of the Flying Dutchman was sung on the stage in New York, and printed in several early songsters there. Our version comes from a singer in a folk club in Manchester, and is generally similar to Doerflinger's. GET UP JACK, JOHN SIT DOWN 'Get up Jack, John Sit Down' was a common cry from the landlord or landlady when Jack had finally spent or been cheated out of all of his hard-earned pay. His seat given to John the landsman, he went back to his ship. The song was collected in America by Frank Warner, who obtained it in New Hampshire from Lena Bourne Fish, whose ancestors had been the original settlers of Bourne, on Cape Cod. As far as we can ascertain it is the only collected version (printed in Lomax). Frank often sings it himself, as do his sons, Jeff and Gerret, but when we first learned it from the singing of Peter Bellamy, (formerly of the Young Tradition) it had changed somewhat from the way the Warners sing it. It was an interesting experience persuading Jeff and Gerret to do the chorus "our" way. [NB: since these notes were written we have discovered that the original song was written in New York by Ed Harrigan & David Braham, for an 1885 theatre production entitled 'Old Lavender'.] THE FLYING CLOUD Perhaps the finest of the tragic sea ballads, 'The Flying Cloud' has appeared in many different collections (e.g. Colcord, Doerflinger and MacColl & Seeger). A confession ballad, (a common theme in broadside publications) its fuller versions tell a gruesome tale of slavery and piracy on the high seas. This one is more condensed, with only one verse referring to the piratical exploits for which the narrator is condemned to death. Published in 'Northeast Folklore', 8, 1966, this version of the song comes from Martha's Vineyard, where it was collected by Gale Huntington. We learned it from the singing of Helen Schneyer of Kensington, Maryland. Emigration conditions The treatment accorded the emigrants on the early packets was not much better than that of the negro slaves on the slave-boats of the Southern Atlantic. The slavers needed to keep their cargo alive, since they got their money at the end of the voyage; the packet companies were fined for the corpses they delivered, but as this amount was only about half the sum that the emigrant had already paid for his passage, it was not much of a deterrent. (From Richard C. McKay: 'Some Famous Sailing Ships and their Builder, Donald McKay', New York: G. P. Putnam & Sons, 1928). HEAVE AWAY , MY JOHNNIES Also known as 'The Irish Emigrant', this is another shanty from the collection of Hugill, who remarks that it is an example of a brake-windlass shanty, which in actual use on a ship was sung to a varying rhythm. The first line was fairly slow, as the brakes or levers were pulled down to waist level, and the next line faster as a second movement brought them down to knee level. Similar versions of the shanty appear in Colcord and Doerflinger. The "Tapscott" referred to in the song was William Tapscott, Liverpool agent for the Black Ball Line (and also, for a time, of the Red Cross Line). Transatlantic dalliance Another hazard for female emigrants was the possibility of landing in the New World pregnant, thanks to the attentions of other emigrants or crew members (sailors being what they are, the latter would seem to have been the more likely offenders). Since these unwanted infants became a burden on the taxpayers of New York, it was at their behest that stiff penalties were imposed on crew members found guilty of such gross moral turpitude. (From Brinnin, pp.19-20). MAGGIE MAY Often referred to as Liverpool's unofficial national anthem, this rollicking song must be known to every Liverpudlian who recognizes the phrase "folk music" (a fragment of it was, after all, recorded by the Beatles). Those familiar with the song maintain adamantly that there exist a number of obscene verses which serve to fill out the missing episodes of the tale; unfortunately, none of them actually know these apochryphal lyrics. The piece is much rarer in print than in oral tradition. Hugill expresses surprise that it is not mentioned by other collectors, but redresses the imbalance somewhat by including several sets himself. PETER STREET It might seem, from the number of such songs on this record, that sailors ashore were in constant danger of losing all their clothes, as well as the rest of their possessions. This probably was the case - if the proliferation of songs on the subject is any indication, they certainly enjoyed singing about such indignities. This particular song is of the "Shirt and Apron" family, and tells essentially the same story as 'New York Girls'. Hugill prints a text entitled 'Jack-all-Alone' but gives no tune. This set comes to us from the singing of Enoch Kent, now living in Toronto, though Tony has changed the words slightly to put the song in a Liverpool context. THE SEAMEN'S HYMN The British sailor, and indeed the British public in general, felt a great loss with the death of Horatio, Viscount Nelson, at Trafalgar. He was a man as much admired by the proletariat as by the aristocracy, and after his death the penny broadsides lamenting his untimely end were among the "best sellers." This hymn comes in us from the singing of Louts Killen, who tells us that it was put together by A. L. Lloyd for a Trafalgar Day BBC radio program. He fitted the words to a shape-note hymn tune in the collection of a Welsh minister. Though not from the period of the packet ships, it does echo an attitude and sentiment common to the time, and we feel that it deserves its place here. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

© Golden Hind Music |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||